A White Teacher Asks His Former Students for Feedback

What it means to apologize-- and be an educator in the real world

Haunted by his eight years in the classroom, podcast producer DJ Cashmere returned to Chicago to interview his former students. Cashmere had been a young White teacher in a majority Black and brown “no excuses” charter school. It emphasized hard-line discipline and high test scores. He wondered: Was it worth it to his students? How had his own shortcomings affected their lives? And what happens when, post-George Floyd, a school rejects its own practices? He explores it all in a deeply affecting podcast called No Excuses: Race and Reckoning at a Chicago Charter School. I was so moved by his students’ honesty and clarity, and by Cashmere’s grappling with his past. Here, we talk about the power of apology, what we get wrong about student “misbehavior,” and what it means not to look away from the truth.

Tell me, why did you want to pursue this project?

I was haunted by these eight years that I had spent in the classroom. Everything I experienced as a teacher was so much harder and more complicated and more impossible than any coverage I had seen. I had triumphs. I messed up a lot. I thought storytelling would be a way to do some healing, not just for me, but for the people I was going to talk to.

This was also a project that had been percolating for years. I had pitched different versions. I had been told previously, "Well, if you're not going to be pro-charter or anti-charter, then I don't know how to sell this."

Oh my gosh.

That was an honest depiction of how the market works. But I'm also grateful that I got rejected so many times because they were less mature versions of the story. I spent two years while I was still teaching working on a book about the school that never saw the light of day. At that point, the thesis was essentially, "Look at this great thing we're doing."

That point about “how to sell” really captures how we talk about complicated issues in our culture, doesn't it? We don't deal with genuine complexity.

We’re used to flattening. Talk to just a handful of students, and there's no agreement whatsoever. That's a subtlety that doesn't just get lost in the coverage, it also gets lost with some of the decision makers. When I went back to my old charter network to report on their transformation, I heard they were deeply valuing input from parents and families. But parents and families don't all agree! One big decision was whether or not to keep the uniform. Parents overwhelmingly favored keeping it. Students and alumni favored eliminating it. One group yes, two groups no, so they eliminated it.

Speaking of complexity, "no excuses" schools, you point out, do have impressive results. A rigorous study found your charter network increased college going by 20 percentage points. Not 20 percent, 20 percentage points. They eliminated the gap between Black and White students’ standardized test scores. Those are real results.

But these come at a huge cost— you share that students felt anxious, tense, ashamed, exhausted. Some regretted going. You talk honestly about how you contributed to those harms, through punitive punishment.

Yes.

How much were your decisions in the classroom about discipline influenced by the "no excuses" culture, and how much by you personally?

It was both. The majority of the consequences I was giving were aligned to how we had been taught. In many ways, they worked. My classroom was orderly. We made it through our lesson plans. We had rigorous academic discussions. When I was teaching theater, we also had a ton of fun. Anything that fell outside of the bounds of behavioral expectations was quashed instantly in the name of allowing everybody to have the experience that they deserved. As a 24-year-old, that wasn't a hard trade-off to make.

Could you have treated students differently, or would that have run counter to the "no excuses" philosophy?

During my last two years in the classroom, I absolutely was treating students in a way that closely aligns with the values that I hold today. I have very few regrets about those final two years. I was leading with trust. I was making the conscious decision to see through "misbehavior" and try to figure out what was underlying it, and asking, "What does it mean to build a relationship?" That was totally okay within the school culture because I was getting fantastic results.

But, huge caveats. In those final two years, I didn't have a full class load. I had two adults in my room every day. I was seven years in and had made a lot of mistakes and had had a lot of mentors.

You make a thorough inventory of your time in the classroom and the ways you fell short as a young White teacher in a majority Black and brown school. You describe feeling tense when a student did something you didn't like. You punished students and took things personally. You were suspicious. You lost relationships because of your behavior.

It was painful to listen to, and I can only imagine it was painful to confront this.

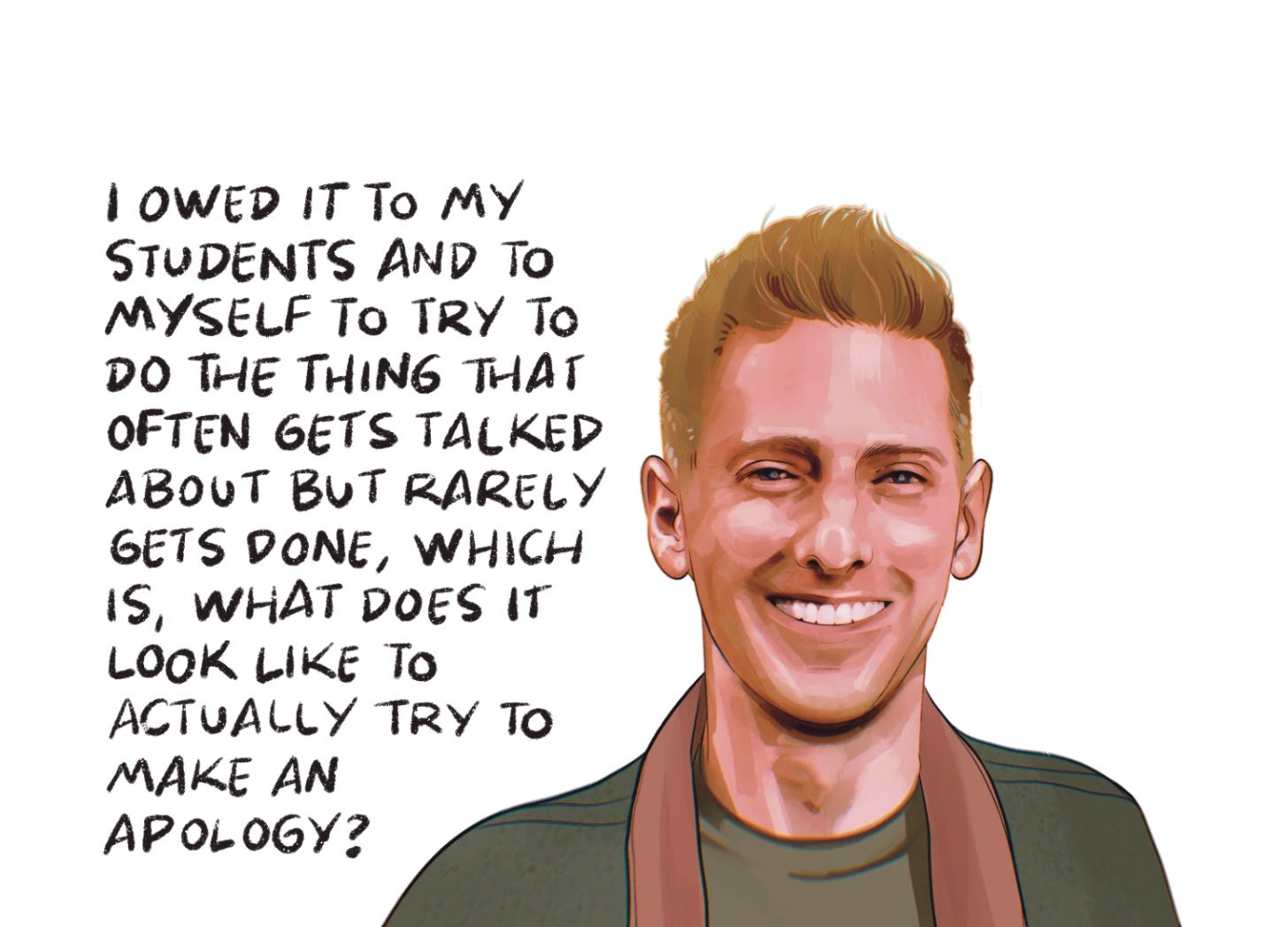

I would be lying if I said that it wasn't uncomfortable. I thought that I owed it to my students and to myself to try to do the thing that often gets talked about but rarely gets done, which is, what does it look like to actually try to make an apology? What does it look like to do a sort of truth and reconciliation process, even on a small scale?

I wanted it to be public because White people don't confront their Whiteness publicly very often in ways that don't feel preachy but just feel true. I hope that some White teachers out there might be able to see themselves in my story and gain something that could be beneficial for the kids that they're serving. If we continue to tell stories about the "achievement gap" or the "opportunity gap" or racism in ways that only ever center the experience of the oppressed person, we're missing an entire side of the equation.

It wasn’t just about race. The mistakes I made in the classroom were also linked to class, gender, my upbringing, the kind of education that I got, how judgmental I was taught to be when I was a kid.

How much of your punitive approach, do you think, was influenced by the fact that you were a White teacher teaching students of color?

I think it was a big part of it. I grew up in America. I breathed in these messages we're all breathing in. In Teach for America, I certainly wasn't explicitly taught, "You should be racist," but I was taught, "These poor kids need your help." So the fundamental dynamic is a savior dynamic.

There were things in the code of conduct about not being late to class— I still think that's a good rule, and I don't think that's racist. But there were also things in the code of conduct, like about hairstyles, which I think were racist. Race was always at play.

Also, I hadn't spent a lot of time in predominantly Black and brown spaces. My first time spending more than an hour in a predominantly Black and brown space was my first day teaching.

You sat down with your students, and you apologized. We have so little practice with genuine apology! V (formerly Eve Ensler) and I had a conversation about this.

What happened in those moments, when you apologized to your students?

It varied. Sometimes there were tears, sometimes there weren't. There was one moment with a student that got deeply emotional, and we decided to keep it out of the documentary because it felt so raw and intimate that it would be exploitative to include it. I bring it up only to say that there were moments that felt like there was really mutual healing happening. A student said at one point something like, "This has been a thousand pounds on my shoulders and talking through this with you today, that weight is lifted."

There was also the almost non-reaction of "Cool, yeah, thanks." Not necessarily intentionally withholding forgiveness, but not being particularly emotionally impacted. The most important thing was to tend to what was needed in that relationship. It was messy and sometimes unsatisfying.

I don't think there's a single person who's taught in the classroom who isn't haunted by something. Because it's an impossible job. Completely impossible.

It made perfect sense that they would carry around that weight because the complexity of their moral landscapes is no less than mine.

Some of your students said they blamed themselves for not standing up more for themselves at the school. I was really taken aback by that. This seems like an unimaginable expectation they had for themselves.

That was one of the most powerful parts of the reporting for me, and one of the things I least expected.

There is this incredible parallel between what I was carrying around and what they were carrying around. They felt like they should have spoken up more. And so did I. It made perfect sense in hindsight that they would carry around that weight because the complexity of their moral landscapes is no less than mine.

It made me think differently about some of the students who were known for acting out, who transferred out because they had racked up so many detentions. For a lot of the kids who were getting in trouble, it was probably a conscious choice. It was probably the way that they could live with themselves and follow their own moral compass.

I had never thought about student "misbehavior" in that way before. It blew my mind. The idea that some of "problem kids" were actually ahead of the rest of us in speaking out, that's a pretty radical lens.

And it totally reframes misbehavior as an expression of self regard and self-respect. It's not about being willfully defiant. It's about having some kind of integrity as a person.

Yeah. So much of my development over the last decade, both in my final few years in the classroom and since, has been about reframing "misbehavior"— as a form of protest, or as a trauma response. A kid who's coming in and has their head down or doesn't have their homework is going through something incredibly difficult in their lives. If you lead with a consequence instead of finding out what's wrong, you may never know that their friend just got shot over the weekend.

So often what's needed is support. It's hard to do in a world of limited resources. But when you are able to do it, it's unbelievable how often it works. I saw kids in my classroom in my final two years who had gotten kicked out all the time and now were never getting kicked out. Kids who would've done really poorly on the test and now were killing it on the test. The only difference was my ability to see past the mirage of the "misbehavior" and try to hone in on the need.

Part of learning to do that was watching other teachers in the building, many of them people of color who were doing that effectively, and trying to mimic them.

By the time I left the classroom, I was like, I literally have no idea what anyone's potential is. I have no idea what's happening in anyone's life. I have been wrong so many times.

Seeing the world through that lens is a tall order. But it's just incredible what people can pull off and how hard kids will work if they think that you see them, if they feel that you see them.

Maybe it's if they know that you see them.

For a lot of years, most kids were viewing me in the threat column instead of the safety column. I can say that out loud without, like, crawling up into a ball because, of course I didn't know that. When was I ever gonna learn that in this society, as a middle-class White kid from the suburbs, who went to an elite college and then did Teach for America? It made total sense I made those mistakes.

Yes.

If you can't hold competing truths simultaneously, you can't grow up.

And it can be really hard to hold competing truths in your mind at the same time. It's unquestionably true that I made mistakes. I've had a chance to make amends for some, and I haven't for a lot. It's unquestionably true that I had a positive impact on a lot of kids' lives, some of those kids, while I was making those mistakes.

If you can't hold competing truths simultaneously, you can't grow up. And there's something deeply pre-adolescent— for me personally— in how I as a White person was conditioned to handle my own shortcomings, which was generally deny and defend.

Look at the popularity of To Kill a Mockingbird and how no one wanted to talk about Go Set a Watchman [Harper Lee's previous version of the book]. The difference between those books is that To Kill a Mockingbird is told from a child's point of view. Go Set a Watchman is told from an adult's point of view.

To Kill a Mockingbird is the most beloved book in America, mostly by White folks. It's a child's view of race. We don't want to grow up. It's painful to grow up. But what we're missing is how painful it is not to grow up.

Yes.

After George Floyd was murdered, the school— like so many institutions— went through a reckoning. It apologized for what it called a racist culture. In 2021, it rolled out new policies, like getting rid of detention, uniforms, rules around hair and tattoos.

The results were mixed. Students were hopeful, but then said it was harder to learn. Students felt more freedom, but it was less safe. Over the school year, violence increased, there were stabbings. Standardized test scores decreased. Black boys were still disciplined at a disproportionately high rate.

Is this an instance of the tension between freedom and safety? Why did things spiral out of control so quickly?

Everyone I talked to had their own theory. Some things that were true: policy changes were made on Zoom before the students were fully back in the building, so I think there was a bit of a disconnect from experiential knowledge of being in a building full of students every day and what it means to make some changes. Big ideas can feel much more doable when you're removed from the doing. That was part of it.

Also, we have a lot of great models for talking about injustice, oppression. It's one thing to take the lens of somebody like an Ibram X. Kendi and critique what was wrong. It's another thing to try to completely change how you run a school system based solely on a critique of what was wrong. It's easier to say what's wrong than it is to build something better.

Yes.

There's a way in which ideology— whether it's "no excuses" ideology or anti-racist ideology— obscures your ability to live in reality.

The idea that you're going to completely uproot systemic racism from a single institution, that still exists within a society where all these problems still exist— it feels not entirely reality-based. I actually think there's a way in which ideology— whether it's "no excuses" ideology or anti-racist ideology— obscures your ability to live in reality.

The ideas sounded great, and people decided to go for it. There were also folks who said, "I thought things were going too far, but I was afraid that I would be labeled as racist if I said something," which is totally predictable given the climate of 2020 and 2021.

In hindsight, what would it have looked like to get rid of the most egregious rules and keep the basic rules? What would it have looked like to go slower? What it would look like for a school system to be run with less ideology, more connection to reality— to have strong values and also acknowledge what you're up against?

One key to developing trust with students was trying to truly understand them and the reasons for their behavior. But looking why students are "misbehaving" seems counter to a "no excuses" framework— now you're finding excuses! Is there room for that empathic, trusting approach within that framework?

"No excuses" was originally intended to mean "no excuses for adults." No excuses for failing kids.

Wow.

This idea that we're going hold ourselves accountable as educators for student achievement, safety, wellbeing, is appealing. Knowing what we know about poverty, gang violence, what students are experiencing from the moment they wake up to the moment they sit down in first period in many cases— what should a school be responsible for?

There is no consensus on that answer. As long as there's no consensus, we will continue to vacillate between various extremes and buzzwords. In a world where millions of students in America are food insecure, without access to healthcare, exposed to violence in their neighborhoods, we struggle to identify what the job of an educator should be.

It's hard to rally people around opposition to something. That’s really hard.

What was appealing about being at [the charter school network] in the early days was there was a really clear definition: we're gonna raise their test scores as much as possible because they really do matter. They are the single best predictor of the quality of the college that they'll get into. Colleges have terrible graduation rates for Black and brown kids unless they're good colleges. So a good test score means a good college, which is the most likely lever to pull to get a better outcome for everything from income to life expectancy. There was a positive vision for the future.

I think what has been lost in a lot of these "no excuses" schools in the last few years is that clarity.

Building around anti-racism, around being against something— it's hard to rally people around opposition to something that no one can agree on the definition of. That’s really hard.

Also, you can measure test scores.

Right. So you hear phrases like "restorative justice," but you don't have significant restorative justice training. The discipline team is now called the culture team, but you don't have three or four times the social work staff. You don't have a school library, a full gym, a football stadium, a theater.

You are experiencing racism just by walking in the doors, relative to wealthier, Whiter schools.

After listening to your podcast, I had a conversation with a man who immigrated from Iraq. He said, “Under Saddam Hussein there was safety but no freedom. For years after Hussein, there was freedom but no safety.” I kept thinking about your podcast.

What does it say that that's the other example that comes to mind in terms of the forces these kids are having to contend with?

Right. When you see this dichotomy between safety and freedom— wealthy White kids aren't given that choice. They just have both.

A lot of the students that I taught weren't dealing with PTSD because the P stands for post. When you are in an unsafe environment daily, it's really hard to learn. There's a temptation to say we have to lead with safety and love. That's true. And you could do that all day and never teach any math. That's not serving them either.

What does it look like to admit our limitations as a first step, and then make a series of choices instead of claim a set of ideals?

It's important to say that everyone I talked to at my old charter school network cared deeply and was working really hard. I think it’s important that we're honest about what's working and what's not. And it's easy to hurl judgments from the sidelines at people who are working under impossible conditions. To frame any debate around schools as being about good decisions or bad decisions being made by school leaders is an abdication of societal responsibility.

I remember the day I left the classroom having the thought that I would never do anything as difficult in the rest of my professional life as being a teacher. And that has been true.

I’d love to hear what you think. Do you resonate with these ideas, from the teacher or student point of view? How does this make you think about debates about education reform? If you’re in education, what struck you about this conversation? Feel free to comment below.

This newsletter is free, but if you’d like to support my work, please forward to a friend! Or pick up a copy of The End of Bias: A Beginning, about how people, organizations, and cultures have reduced bias and become more fair and humane.

YES - teaching IS hard. MORE of this - more on the complexities, the nuance - more on how it took him 7 years to find his groove.

MORE on the pressure to raise test scores - because it is what is possible (in some cases) - and MORE on how social failures (persistent poverty, income inequality, systemic racism) impact education. Educators and schools are (it seems) tasked with overcoming these challenges even if the greater society ignores or even exacerbates them. It's pretty logical, then, to think about what a school CAN do - like address test scores to expand possible student opportunity.

Schools might also become community centers or provide free breakfast and lunch - but that requires funding.

When schools ask for money, they are often told to "show results" and that means those tangible, measurable test scores.

Lots to digest here - and then there's the reality that while policymakers "figure it out," kids are in school now - they can't wait for consensus to emerge.

Holy smokes, he articulates the intense complexities so well! Safety vs freedom (and the ways that feeling safe contributes to learning and success); reactionary "fixes" that feel good in the moment but that carry loads of unforeseen and often harmful consequences; the way ideology obscures our ability to live in reality (what an amazing way to describe this!); the way there's very little room to ask questions in good faith or talk openly about concerns or what's not working, because there's so much fear about being branded and cast out.