Curiosity is the Real Resistance

Undemonizing our opponents, and what it means to be a "real Latina."

Dear friends,

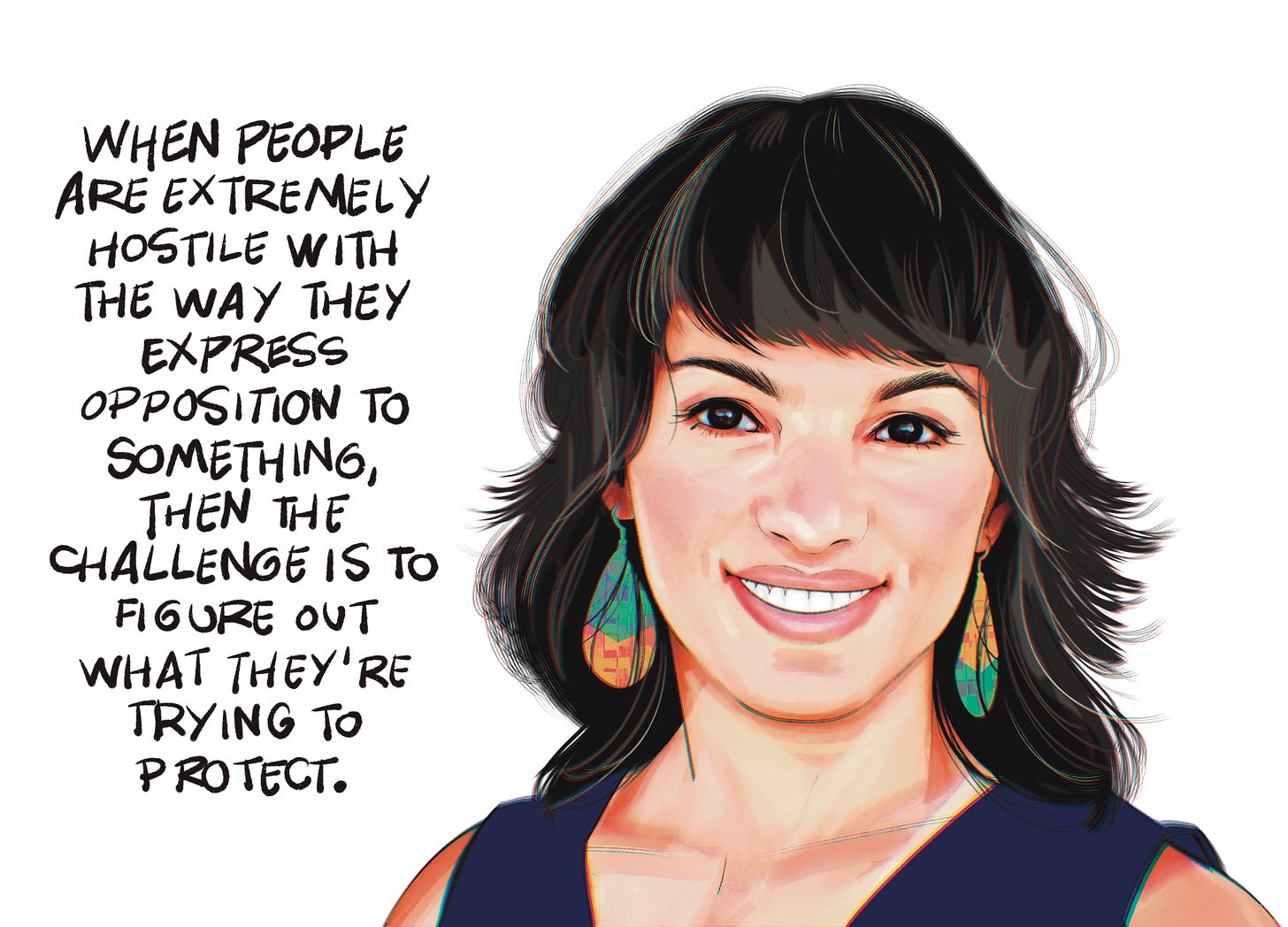

If Mónica Guzmán’s book had a soundtrack, it would be George Michael’s 1990 album Listen Without Prejudice. Mónica is the outspoken, liberal daughter of two beloved, conservative, Trump-voting, Mexican immigrant parents. Her mission: to persuade us all to get curious about our opponents. Mónica’s book I Never Thought of It That Way is a profoundly hope-giving repair manual, a guide to building bridges over political crevasses. Here, we talk about the perils of dehumanizing our foes, the dead end that is personal branding, and what it means to be a “real Latina.” A longtime journalist, Mónica is Senior Fellow for Public Practice at Braver Angels, the largest bipartisan organization aimed at depolarizing the U.S. I’m so excited to share this conversation with you! I’d love to know what you think.

Your project is encouraging all of us to loosen the tight grip we have on certainty— on our need to be right— enough to let in another person's point of view and engage with it. That strikes me as profoundly countercultural! We valorize strong opinions. We don’t see a lot of op-eds going, “Here’s what I think, but I can totally see how someone might disagree.”

I do see this work as countercultural. I see curiosity as the real resistance. We're in an era of really strong activism and urgent need for change. So there's a glory to holding up your sign and being clear in your convictions and being ready to fight.

Here's the bigger picture that I see. I see communities of interest pushing for change as being sort of mountainous islands. At the center, at the top of that mountain, that's where the most devoted and uncompromising people stand. And we need them up there shouting.

But every community needs a harbor. So down at the coastlines, that's where the mediators are. When visitors from other islands want to wander around, they need someone to say, “Welcome. I want to hear you. Do you want to hear me? Let's talk.” Our culture spotlights the people on top of the mountain as if they're the only ones that matter.

If you believe that you are better than this other person, that will come across. And that person will feel like the entire conversation is a test of their survival and dignity

Yes.

Change is actually not possible without an interpretive and connective layer. Because when you believe really strongly about one thing, it's gonna be hard for you to listen to countervailing points of view. If your goal is to persuade, that's a weakness.

In other words, we need the fighters. But if the fighters are all we have, then we will just actually kill each other. We need the mediators, we need the curious. It's an important role. To be confident and uncertain-- that takes the most courage of anything.

I love this image. If you want people to come onto the mountain from somewhere else, you have to have a harbor where they can enter without getting smacked down.

Exactly. I honestly think that the most effective activist is the one that can hold convictions while also switching immediately to uncertainty and curiosity, so the person who approaches them can actually hear them and be heard by them.

Yes.

That's when the idea can really transfer.

And that's a very complicated choreography to do. Harder than just projecting one's ideas loudly and with certainty.

Right. Right now, the people who project their ideas loudly with certainty are mostly getting all their likes and shares from people who already agree. And we have to ask ourselves, what's the goal? If the goal is a feeling of belonging and a feeling of purpose, then go right ahead.

But if that goal is actually to change the world, and have persuasion be effective, then this is not enough.

This connects to a conversation I was in about education policy. We were talking about how some parents are panicking about the history of racism and white supremacy in our country being taught. I wondered out loud: if I want these things taught, is there a way to meet that other side by looking at the emotion beneath that terror of history?

A hundred percent. We want to defend and attack and shame. Those build walls. When people are extremely angry and even hostile with the way they express an opposition to something, the challenge is to figure out what it is they're trying to protect.

We think we're going to find the same monster behind every conversation.

Yes.

Get curious about that. The way to do it is to ask about people's concerns. In a non-judgmental way, which can be difficult. But it is only psychologically difficult. It is not technically difficult. It’s, “I get the sense there's something that really feels off for you about this, and I want to understand. What are your concerns about history being taught this way?”

And then, can you actually listen to their answer? It means nothing if you can't actually give enough space for that answer to come out. If people are angry, they might say it with a bad tone. Can you still stay curious? Can you listen for what's really going on? Then collaboration becomes possible.

I asked this in a group of left-leaning progressives, and Mónica, I could feel the resistance in the room to the idea of trying to understand the other side emotionally, these parents who are so terrified of Critical Race Theory that they're taking their kids to different school districts. There’s something almost threatening about acknowledging these are people who are having an emotional experience.

The reaction I see is eye rolls, which comes from, “I don't need to ask them. I already know what they think. They're sucky people. What is there to learn from them?”

That certainty is understandable— in the places where we watch people talk about these issues, the meanest voices tend to dominate.

We need the fighters. But if the fighters are all we have, then we will just actually kill each other.

So we think we're going to find the same monster behind every conversation. And we forget that when you actually talk to people, you're talking to an individual person, not an ideology. Your book is all about that. When you treat a human being like the label and all the associations you have with that label, that's a really pernicious form of spread-out certainty.

Right.

The way is to get around that is to say, “I'm not approaching an invalid idea. I am approaching a valid person. All people are valid. I am okay enough with all people to engage with them. They may have bad ideas, but they are still a valid person.”

That's the way to make sure we never dehumanize. Too many of these battles have gotten to the point of “righteous dehumanization”— like, I'm dehumanizing for a good reason. I treat that person like scum because they treated me like scum. And that cycle just never ends.

Do you know the poem by Yehuda Amichai poem ”The Place Where We Are Right”? I love this poem so much. It starts “From the place where we are right/ flowers will never grow/ in the spring./ The place where we are right/ is hard and trampled/ like a yard….”

It connects to your idea of certainty. There's no room for anything to grow there.

Exactly. And yet we think that is the place to be. What more could we need? We think these other people are evil or crazy—or wounded, which is an interesting one.

This phrase keeps echoing in my mind from a civil rights lawyer named Connie Rice, who I write about in my book. She sued the LAPD for discrimination for 15 years and then started working with them to change from the inside. She said something I'll never forget: ”You can't persuade people you hate.”

It’s impossible. The word I prefer is condescension. If you believe that you are better than this other person, that will come across.

People understand how you feel about them.

Yes. And that person will feel like the entire conversation is a test of their survival, dignity, ability to defend themselves.

We will always judge, we will always assume, but we can be aware. People say this work is hard. I think it’s psychologically hardest with yourself. It's hard to think we need to work on anything in ourselves.

There's an idea that we should have figured out all the answers already. But we’re all evolving. It’s why I resist the idea of personal branding, which is about controlling how others see you and making sure you’re consistent and legible at all times. If you’re always trying to control others’ perceptions, how can you ever grow? How can you ever be vulnerable or make a mistake? The writer Jenny Odell said, “Creating your personal brand is like making your own coffin.”

<Laughs> Imagine if that's the way we treated our friends! “I'm delivering value to you that you can expect and define.” We don't do that with our friends because we're building actual human relationships.

Exactly! In your book, you also share grappling with whether to correct the record about your family. Someone wrote publicly that you’d come from a “struggling Mexican immigrant family.” But that wasn’t the case. And you worried you might not be seen as a “real Latina.”

I almost didn't share that story. I was scared about it.

Can you say more?

[I was] somebody who was in Mexico and didn't have to leave. My family left because my dad got this opportunity to work at this company, on their IT department. It was his dream to move to the United States, but it was a much more sort of middle to upper class immigration experience. It wasn't crossing the border illegally.

A part of me thought, man, if people read this about me, then whatever disgust is applied to people with more privilege will be applied to me, and it stains who I am in the eyes of others. I mean, that's a lot of self-loathing, right? Why would I assume that?

But stereotypes become traps. You feel you have to conform or else you cannot identify as that thing. I have felt that, as a Latina. My daughter was born with blonde hair. I have a White husband. Oh no! <Laughs> You know, I’m walking around with her going, well now definitely people won't see me as Latina. But I can tell you, there are blonde Mexicans!

The full picture of any country is so much bigger than what another country sees. Just telling the truth about, hey, we didn't actually struggle in our immigration at all— not even close— does that then take the spotlight off the struggle, and how important it is to take care of the most vulnerable people? [Part of me thought] maybe I should lend weight by holding up the lie for just a minute. A little white lie. Whoa.

Where are you at now with discomfort about people knowing that part of your story?

It is worth telling the truth, but it's better to also talk about the discomfort, the honest context.

I shared things in my book as well I wasn’t sure about including. I learned over the process of writing my book that I had enslavers in my ancestry. I was like, do I want to include this? But I had to include it.

I think we all want to walk around as if our history is none of our personal histories. But that's impossible.

Completely.

You descended from people who owned slaves. Was there any good to them? Do you believe that stained them forever? Is it possible for humans to be more than any bad thing?

Those are really difficult questions, particularly with true moral abominations. I have a deep conviction that the human is always stronger and bigger. I know that might be hard to hear for some folks, but I do think that has to be the case for change to be possible.

Your story made me think about how one of the critical ways of reducing stereotyping is actually increasing the complexity with which we see that group.

There's a study I wrote about where researchers manipulated whether a group was seen as homogenous or very diverse. And when the group was seen as more diverse, people discriminated against them less. Your story may help others see the Mexican immigrant community as much more diverse than they realized, which actually reduces stereotyping and prejudice!

It behooves us all the more to try to share our truths with each other. We start to think that everyone's the same because everyone's afraid to show that they're different.

I think we all have parts of ourselves that we fear others knowing. We worry we won't be loved. Or accepted. I think it comes down to that.

And you need internal security to do that— confidence that who we are has something to teach, has something of value. We're valid people. Our truth is okay. Our truth is good. Even if we harbor bad ideas, let's find out which ones they are. Let’s go! We can't hide ourselves anymore. We’re doing a lot of that.

💫 Announcements 💫

*I’ll be in Washington D.C. this weekend for a public talk this Sunday, January 29th. Free and open to everyone. You can sign up here!

* Book clubs reading The End of Bias: A Beginning can sign up here for a 30 min “Zoom with the author.” I’m excited to meet you.

Good stuff. This reminds me of some of the things Anand Giridharadas talks about in his book.

One thing this makes me think of is the desire for activists to use language to control the discussion around a topic. For example, people who are in favor of access to abortion call themselves "pro-choice" and people who are against it call themselves "pro-life". Conversely, they might call those who disagree with them "anti-choice" or "pro-murder".

While this sort of language might be useful for rallying those who are already believers, it makes it impossible to actually have a conversation with someone who disagrees with you, because you can't even agree on the terms to use.

Or to use another example near and dear to my heart, back in the day many animal activists would use slogans like "meat is murder". I agree with that 1000%, but saying that at best achieved nothing, and more likely acively hurt the movement. The vast, vast majority of people don't agree with that statement, and simply repeating it over and over will not change their minds. The only way to make an impact is to meet people much closer to where they're at.

Fortunately the animal advocacy movement has largely moved on from that, but many other movements are still obstinate about their language, even when it alienates and polarizes people who disagree with them.