Dear ones!

Greetings from the molten center of our republic. Welcome to the inaugural issue of Who We Are to Each Other, monthly tidings from the quest for more humane, fair, and life-giving ways of being with one another. (If you’re receiving this in error, please accept my apologies and let me buy you a scoop of mango sorbet.) To begin, I’ll be sharing never-before-seen conversations with some of the brilliant thinkers I feature in The End of Bias: A Beginning (which is just out in paperback!).

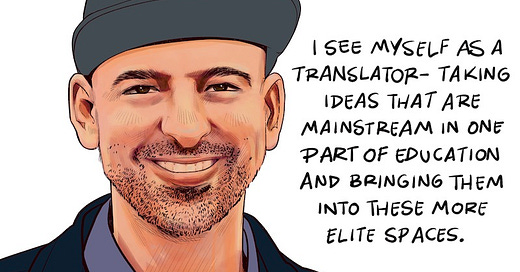

In honor of the start of school, today’s chat is with visionary educator Dr. Federico Ardila. I felt deeply moved by our conversation and by what feels like a sacred dimension to his work. His principles apply to human relationships more generally, and I hope you’ll be as inspired as I was. A Colombian mathematician, Ardila is a professor at San Francisco State University, creator of the ECCO math conference in Colombia, DJ with the collective La Pelanga, percussionist, and co-founder of the marimba de chonta band Neblinas del Pacífico, bringing musical traditions from the Afro-Colombian Pacific to the U.S.

Following is our edited conversation about his radically inclusive classrooms— and the beauty they make possible.

Jessica Nordell: You describe how important a sense of community is for students. That wasn’t your experience coming to the U.S. as a math student.

Federico Ardila: I grew up in Colombia. Over there, I was in the majority; the assumption is that a Colombian mathematician looks like me. I felt included. But when I came to the US, I experienced a very big cultural difference. I wasn’t part of mainstream American White culture, American Black culture, American Latino culture. Others didn’t do anything explicit to exclude me, but I felt I was not a part of it. In nine years [of undergrad and graduate school], I worked on homework with others only twice.

I also found this macho way of doing mathematics in rooms with a large majority of men, it doesn't feel very good. I probably participated in it in Colombia and didn’t notice. There’s often a competition to be the alpha. Now, when I go to a top research university and I sit in a talk, I’m struck by these competitive environments where grown men are trying to demonstrate how smart they are—and even trying to belittle, to make the point that what the speaker is doing is not that interesting.

It sounds like an environment where everyone is trying to dominate everyone else.

Yeah. I was trained in educational spaces that were elitist by definition. They were designed to figure out, of the elite, who's the super elite. The motivation is for you to prove that you are more elite than the other elite people. This eliteness is closely tied to the opportunities and access. Old school professors could be really mean and put people down. And, if you put it more honestly, there's a fair amount of emotional abuse in the way that people communicate in some academic spaces.

We often have very narrow ideas about who are the good students and who are the bad students.

How do you create the opposite—a truly inclusive math environment?

A lot of it is very granular. Usually in education the professor has all the power. I try to make sure that the power is shared. There’s also a really human side– how do you create a space of human respect and human connection?

In most mathematical spaces I create, before you arrive there’s a community agreement. Other conferences have a code of conduct—useful, but it often sounds like policing. We focus on what we’re trying to create, rather than what we’re trying to prevent. At first people are often a little confused, but I ask them to get in pairs, read it out loud, talk to each other, decide what it means to them, and how they can put it into practice. People resonate with different parts. It sets a tone and a culture—this initial culture-setting is important.

I also DJ and I spend a lot of time creating atmospheres that feel comfortable. The awkward quiet math class is not welcoming to anyone. One simple practice is to have some nice music playing when students arrive. As soon as I did this, I thought, “Why should I be subjecting them to my music?” So now I have students bring in music that is meaningful to them, and ask them to tell us a little bit about the song if they would like to. I am surprised by how much students want to share about themselves.

Your approach seems countercultural— especially compared to the math education I received! For instance, you give students the freedom to pursue personal math interests.

We often have very narrow ideas about who are the good students and who are the bad students. Very often those are tied to a particular kind of evaluation—students who can do well on tests or solve problems quickly are rewarded especially.

When you assign open-ended work, you find that some of the students who do well on tests really struggle. But this is the work people do in real science! You also see students who got low scores on tests, but they’re able to really show a very different kind of work when it’s something they’re committed to. When they are given the room, students bring their own personal interests into their work, and do deep and beautiful work that is really theirs, and that I could have never planned for.

You mentioned power. How do you shift power in the classroom?

For example: boys are overconfident. After teaching for 20 years, I’ve always seen men convince ourselves that we’re right more easily, and that makes us more comfortable to speak out. Sometimes we speak so much, we sound right, even when we’re not. That’s a dynamic: male voices are listened to more. There are many similar power dynamics. I try to put some structure in place—little tricks. For example, when I ask a question, I say, “Let me see three hands.” I can guess who the first will be, maybe also the second, and then after an awkward silence, there’s a third person who doesn’t usually participate. Then I call on students in reverse order. It changes the dynamics of who speaks. By the end of semester, everyone’s talking. A few structural interventions make a big difference. I learned this and many other useful interventions from my SFSU colleague Kimberly Tanner.

I have to say that a lot of my best ideas are not my ideas. Within the context of an educator in a public institution, my ideas are actually not that strange. I have a lot of friends who are public school teachers in underfunded schools in the Bay Area, and I learn a lot from talking to them. At that level it’s well acknowledged that education is very human. To be honest, sometimes I see myself as a bit of a translator—taking ideas that feel very mainstream in one part of education, bringing them into these more elite spaces.

These ideas are not compromising quality or excellence. Inclusive spaces are not remedial spaces. I really have seen how these spaces lift everybody up, sometimes in ways you don’t expect. One attendee at the conference we organize wrote about how this was the first time he felt comfortable being openly gay at a math conference. We’d never talked about inclusion along sexual orientation. But the atmosphere made it so that he felt welcome.

Not only are we going to be more inclusive, but I really do believe that science will benefit from this.

How have you seen that benefit playing out in math?

When we follow the mainstream idea that mathematics is independent of culture and it's the universal truth, then it sounds very strange that it should matter who does it. But I've found that when I really try to get students to bring their full selves—and not set aside the fact that they're a parent, or an immigrant, or Latinx, or whatever—that sometimes gives rise to mathematical insights.

I had never heard that question in a math setting: what does this field not do well? That's a very mathematically mature question to ask.

Can you share an example?

I taught this graduate course in Representation Theory once, one of the most advanced classes mathematically that we offer. I had a large and very diverse group of graduate students in the class.

While preparing, I found out that “representation theory” is also the name of a branch of cultural studies. And I just told students one day, "Hey, have you heard of representation theory as part of the humanities?" They hadn't. Oversimplifying, representation theory in cultural studies is about how groups of people are represented—in the media, or in pop culture, or in our case, in mathematics. For example: What does the mathematical community assume about Latinxs? And as soon as my Latinx students asked themselves that question, they had very strong feelings about it, because they've experienced it. The representations of Latinxs in math is something that they know they need to be critical about.

And then something clicked, and they were like, "Wait, how come we don't think about mathematics in that critical way?" In mathematics, we're not taught to think critically about the material. But what if we ask, okay, what do representations in mathematics not do well?

I had never explicitly heard that question before in a math setting: what does this field not do well? That's actually a very mathematically mature question to ask.

And this ended up leading the students to discover some mathematical results that we hadn't thought to ask about this math theory, through their applying this critical lens coming from the humanities.

Fascinating. Other examples that come to mind?

This becomes even more important when we think about how math is applied. I think many mathematicians wish that our work was not applicable, so that we wouldn't have to think about the ethical questions that arise when math gets applied to war, or to security, or to predictive policing. How math is applied is very much a function of who is doing math, and what questions they are asking, and who's funding them.

A new set of perspectives means we can ask new, important questions that usually feel very poorly understood.

For example, mathematician Maria de Arteaga, who I knew as a student in Colombia, did a research project where she got in contact with the police department in El Salvador and got a hold of decades of historical records of cases of sexual violence. She did a statistical analysis and was able to discover patterns surrounding sexual violence that hadn't been noticed before, and that could inform policy. I hadn't heard of mathematicians engaging in research like this before.

I always used to think that I didn’t like conflict. But it’s easy to not like conflict when everything is designed for you.

Audre Lorde said, “Let difference do its work.” We often hear the message that we’re all the same and we need to find our commonalities. But no, she tells us, our differing perspectives should be acknowledged and used to our advantage.

With your students, how do you balance the tension between recognizing group identities and seeing students as individuals?

I think about that tension constantly. I didn’t think much about these issues until I landed at a department where I’ve been the only professor of Latinx heritage, while over a third of our students are Latinx. I started noticing how important it was for many of my students that I was there. But my experience is very different. A large percentage of SFSU students are first generation college students, many from under-resourced public schools. I was a role model, but also, I had a lot more support and access than my students were offered.

Now I’m listed as one of the Latinx mathematicians in this country. What does that even mean? There are so many ways to be Latinx in this country. There are so many ways identity shapes experience, but so many that it does not. You don’t want to over-simplify anyone’s experience, or reduce them to a couple of aspects of their existence. At the same time, race, gender, and many other identities play such an important role in the way U.S. society is organized. What does that mean for individuals?

In Colombia, I grew up being in the groups in power. I always used to think that I didn’t like conflict. I liked agreement. But it’s easy to not like conflict when everything is designed for you. And there’s a reason I could get away with being a conflict-averse person there: the world didn’t conflict with me. That changed when I came to the US, and I’ve slowly learned that sometimes conflict is necessary because it’s the only way things will change.

Ultimately, what I try to do is to make room for my students, and make sure they know they will be listened to and taken seriously. We do not need to shy away from discussing aspects of our identities that may lead to discomfort. But in the end, each student decides what aspects of themselves they want to bring into our shared mathematical spaces. 🪴

✨ Announcements ✨

I’ll be touring both virtually and in-person this fall, starting with the Green Mountain Book Festival in Burlington, VT, on Sept. 24th. Featuring the incomparable Ruth Ozeki! Check jessicanordell.com/speaking for upcoming events.

Free book club guide and synagogue book club guide are now available.

The End of Bias: A Beginning is now out in paperback. Consider buying one for an educator you love!